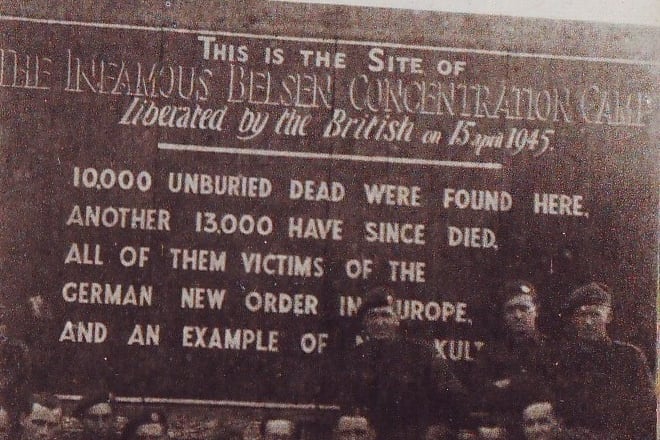

The concentration camp Bergen-Belsen was liberated on April 15, 1945, by the British 11th Armoured Division.

The sights that greeted the Allied troops were hellish. Over 10,000 corpses lay strewn around the camp unburied, and the 60,000 prisoners still alive were seriously ill.

These nightmarish and apocalyptic scenes were described by RAF medic and Monmouthshire man Vincent Leslie as, “Definitely my worst memories of the war.”

Vincent joined the RAF in 1941and underwent his initial training at Henderson barracks, Halton camp, before the course of the war took him throughout Europe, to places such as Belgium, Holland and France.

Vincent was involved in the final Allied push to Germany where he helped to liberate and care for the survivors of Bergen-Belsen.

Situated near Hanover in northwest Germany, Belsen was built in 1940 as a prisoner-of-war camp for French and Belgian prisoners. In 1941, it was renamed Stalag 311 and housed about 20,000 Soviet soldiers, 18,000 of whom were estimated to have died from hunger, cold, and disease.

The camp was converted into a concentration camp and placed under SS command in April 1943.

Initially, Jews with foreign passports were kept there, intended to be sent overseas in exchange for German civilians who were interned.

Although very few exchanges were made, about 1,500 Hungarian Jews were allowed to emigrate to Palestine, and about 1,500 Hungarian Jews were allowed to emigrate to Switzerland.

In December 1944 SS-Haupsturmfuhrer Josef Kramer became the new camp commander.

Known to history as the ‘Beast of Belsen,’ Kramer had previously spent time at Auschwitz-Birkenau, and under his control, conditions at Belsen worsened.

Originally designed to hold about 10,000 inmates, large numbers of additional prisoners were moved to Belsen from other camps further east that were under threat by the advancing Soviet forces.

The resulting overcrowding due to the influx of about 60,000 extra prisoners led to a collapse of basic services, such as water, food, and sanitation, resulting in a vast increase in disease and malnutrition.

One of Hitler’s most famous victims 15-year-old Anne Frank, and her sister Margot, died of typhus just weeks before Belsen was liberated, after an epidemic had swept through the camp.

Although Bergen-Belsen contained no gas chambers, more than 35,000 people died of starvation, overwork, disease, brutality, and sadistic medical experiments in a camp where the average life expectancy of an inmate was nine months.

After his mother was sent to Auschwitz to never return, Holocaust survivor Moshe Peer was sent to Belsen in 1942 at the age of nine, in his book Moshe recalls, “In Belsen there were pieces of corpses lying around and there were bodies everywhere. Some alive and some dead. Bergen-Belsen was worse than Auschwitz because the people were gassed right away, so they did not suffer for a long time. I remember in Belsen, that Russian prisoners were kept in an open-air camp and were given no food or water. In Belsen, some people went mad with hunger and turned to cannibalism.”

The BBC’s Richard Dimbleby who accompanied the British troops as they liberated Belsen, famously described the visions of Hell that lay in wait for a watching world with the words, “Here over an acre of ground lay dead and dying people. You could not see which was which... The living lay with their heads against the corpses and around them moved the awful, ghostly procession of emaciated, aimless people, with nothing to do and with no hope of life, unable to move out of your way, unable to look at the terrible sights around them... Babies had been born here, tiny wizened things that could not live... A mother, driven mad, screamed at a British sentry to give her milk for her child and thrust the tiny mite into his arms, then ran off, crying terribly. He opened the bundle and found the baby had been dead for days. This day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life.”

As the first major camp to be liberated by the Allies, the event received enormous press coverage, exposing to the world for the first time the horror that was the Holocaust.

As a final act of defiance, the last of the Germans to leave cut the water supply, making it difficult for the Allied troops to treat the ill prisoners.

Sixty-thousand prisoners were present at the time of liberation, and despite massive efforts to help the survivors, about 500 people died daily of starvation and typhus, until their number amassed nearly 14,000.

Mass graves were dug to hold the thousands of corpses of those who perished, and today all that remains on the site of the former camp is a graveyard.

Michael Bentine wrote about his encounter with Belsen, “After VE Day I flew up to Denmark with Kelly, a West Indian pilot who was a close friend. As we climbed over Belsen, we saw the flame-throwing Bren carriers trundling through the camp - burning it to the ground.

“Our light Bf 108 rocked in the superheated air, as we sped above the curling smoke, and Kelly had the last words on it. ‘Thank Christ for that,’ he said fervently. And his words sounded like a benediction.”

Vincent’s son George Leslie, kindly agreed to share the memories and recollections of his late father’s wartime experiences, including a very revealing photo album/diary which Vincent complied during the war.

George told the Chronicle, “Dad volunteered to go and help out in Belsen as very few had the stomach for it. How he remained sane after his time there is a mystery to many, but he never let his experiences harden his heart, or make him cynical. He always saw the best in people and had a zest for life, right until he passed away some 20 years ago.

“He was never reluctant to talk about his war years and I remember he told me that he initially wanted to join the RAF as a member of an aircrew, because back then he realised that he would be called up any day, and Dad’s rationale was that if he volunteered he would have some say in what section of the armed forces he could serve with, rather than be chucked in with any old mob.

“However, he failed his fitness exam to join an aircrew because they said he was flat-footed, but he was told that if he had set his heart on joining the RAF, there was a position in the Medical Section.

“Dad always said afterward that he was glad he failed his fitness exam, because being a medic, he knew only too well the wounds and deaths that a lot of the aircrews suffered during the war.”

After a period of training, Vincent was sent straight into the thick of the war in Europe, and his photographs capturing that period reveal such sights as France as it was in 1944 - devastated and in ruins, about which he wrote, “France as we found it in 1944, a smoking fly-infested, stinking dirty Hell,” and then later on Vincent writes, “The sun shines, the streets are cleared, the dead are buried and life goes on gain, but there is a strange silence, the stench of death is everywhere.”

Perhaps one of the most striking photographs in Vincent’s collection is the one that captures three of the most evil men ever to curse the earth with their vile tread - Adolph Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Heinrich Himmler, all enjoying a leisurely stroll together.

In Vincent’s photograph album, the picture in question lies below a simple inscription that reads, “Here they are, the cause of all the trouble.”

George recounted to me how this particular picture ended up in his father’s private collection, “My father came across this photograph on the person of a dead and high-ranking German officer. Obviously, it’s not the sort of thing you come across every day, so he decided to keep it and put it in his album for prosperity.”

Regarding his father’s time in Belsen, George revealed, “One of my dad’s main roles in the camp was to act as a food monitor. Because most of the prisoner’s digestive systems were in too weak a state from long-term starvation to handle much food, their stomach rejected it with vomiting and diarrhea.

“My father was one of those responsible for making sure the inmates were only given a certain sort and amount of food that would be easier for their weakened and under-nourished systems to digest.

“Of course, this didn’t work in a lot of cases, which although upsetting, never deterred my father from trying to help whenever and wherever he could.

“For example, because of the environment they were in, a lot of the boys started boozing and going to what they used to call ‘bad houses.’

“However being in the medical services and having prior experience of treating a lot of what his friends accidentally picked up in these ‘bad houses,’ dad would always say he had much more sense, and spent his free time going around the towns and villages asking people for any spare blankets, that they would then in turn give to the women at the camp who would make dresses out of them.”

Towards the end of our chat, George revealed one of the stories that stands foremost in his mind about his father’s war years, “I remember once my father telling me that during his stay in Holland, he became friendly with a woman whose husband was a very talented pianist. The Germans had apparently got wind of this and they had a piano they wanted him to tune, to which he replied, ‘I only play the piano, I cannot tune them.’ The Germans did not believe him and demanded he tuned it again and again until they got sick of asking and decided to cut off his fingers as punishment.

“Not long after the Germans accused his wife of having something to do with a tyre that was taken from one of their cars. Consequently, because she refused to admit to a theft she was not responsible for, they shot her child.”

A timely reminder, if any were needed, of why the Nazi regime had to be stopped, and why the sacrifice and contribution Vincent Leslie and millions of others made to that end, should never be forgotten.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.